KCNMA1-Linked Channelopathy

[The text below is meant for a general audience. There is also a comprehensive published review of KCNMA1-linked channelopathy available, written for the scientific and medical community. A French translation of this page is available here.]

What is a Channelopathy?

A “channel” in this case is basically a tunnel which allows one or more specific “ions” (charged particles such as sodium, potassium, chloride, and others) to go through, but only under very specific conditions. The cells that make up our body contain many different types of ion channels on their surface that permit ions to flow in and out of cells. Ion flow is tightly regulated and is critical for the bodily functions that humans require to live and stay healthy, such as controlling the electrical activity of the brain, muscle, and heart. When the activity of these ion channels is altered, people can develop symptoms associated with a wide range of disorders known as ‘channelopathies’. The type of symptoms experienced by a patient depends on the type of ion channel affected because different ion channels serve different functions and are expressed in different locations throughout the body. Channelopathies are typically the result of genetic defects (mutations), however some channelopathies can be caused by medications, drugs, poisons, or autoimmune diseases. Here is a page with more details about channelopathies. The article is written for scientists. But look at the long list of channelopathies in Table 1.

What is KCNMA1-Linked Channelopathy?

It is a medical condition in which most patients can have epileptic seizures, involuntary abnormal movements, or both. Other symptoms can also occur. It is caused by certain defects (mutations) in a gene called KCNMA1. The “KCN” part of the name is short for “Potassium Channel”. “K” is the abbreviation for potassium in the table of elements. The “MA1” part is the name or abbreviation for the specific kind of potassium gene and channel affected. For example, other disorders are caused by mutations in KCNA1, KCNQ2, KCNQ3, KCNJ2, etc. We have compiled a comprehensive review of KCNMA1-linked channelopathy for patients to take to their neurologists.

What other medical conditions and symptoms are associated with KCNMA1-Linked Channelopathy?

KCNMA1-linked channelopathy is a syndrome, meaning it is a combination of symptoms that occur together. There is a large variation in the number and severity of symptoms experienced by patients with this condition. Many people with this diagnosis have a movement disorder sometimes called ‘paroxysmal non-kinesigenic dyskinesia’. Other patients can have epileptic seizures of various kinds. Some can have both movement disorders and epileptic seizures. In addition to these two conditions, many also have developmental delays and other neurologic symptoms.

Paroxysmal Non-Kinesigenic Dyskinesia (PNKD) Type 3

One of the common symptoms in people with certain KCNMA1 mutations consist of very sudden-onset movement problems. ‘Dyskinesia’ is a medical term which simply means abnormal movements. The term ‘paroxysmal’ means that it can start very quickly and the symptoms come and go, with normal periods in between. Lastly, ‘non-kinesigenic’ means that the abnormal movements are not ‘triggered’ by certain particular movements, as can occur in other forms of dyskinesia. There are at least three different genes that are associated with this type of movement disorder. Mutations in KCNMA1 were the third to be discovered, which is why it is sometimes called PNKD “Type 3”. The attacks of dyskinesia can last a few seconds to minutes before stopping. Some patients can have up to many dozens of attacks every day. People move normally between attacks. The muscle dyskinetic attacks can take many forms, and can consist of twisting, stiffening, or incoordination of one or more parts of the body or even the entire body. In some, they may be unable to move, speak, or otherwise respond. However, people are conscious and aware. Because the movements can take many different forms in different people, they are sometimes given a more specific name depending on which particular form of abnormal movement is seen in that person. These include: chorea, atonia, dystonia, and others.

Drop Attacks

Another characteristic symptom for some patients with KCNMA1-linked channelopathy is called ‘drop attacks’. During these attacks, patients suddenly lose muscle control such that they can fall to the ground without warning. In a drop attack, the muscles of the arms and legs can be either tense or completely limp but otherwise unable to move voluntarily. Other terms sometimes used for drop attacks are atonia or akinesia. Sometimes the mouth or tongue can make strange movements during a drop attack. The duration of these attacks can last up to 20 seconds and can occur many times a day. Drop attacks are often confused for epileptic seizures because there are indeed epileptic seizures which can look similar. Note that the term “drop attack” can be confusing because it means different things in different settings and there is not a well-defined medical meaning for this term.

Epilepsy

Many children and adults with KCNMA1-linked channelopathy have epilepsy, which in general is a term used to simply describe someone who has had more than one epileptic seizure. An “epileptic seizure” is a term used to refer to seizures which start in the brain and are due to abnormal brain electricity (there are other disorders which can have ‘non-epileptic’ seizures, but which otherwise look the same as epileptic seizures). In general, seizures in those with a KCNMA1-linked disorder involve the “whole brain”, and specialists refer to this as a “generalized” epilepsy. There are many different types of epileptic seizures which one might have. Some epileptic seizures consist only of very brief (less than a second) muscle jerks (‘myoclonic’ jerks or myoclonic seizures), seizures with whole body stiffening and unconsciousness (‘tonic’ seizures), seizures with sustained rhythmical jerking movements and muscle stiffening (‘clonic’ seizures), or seizures where one simply pauses what they are doing, but are non-responsive and can’t see, hear, and are actually unconscious (‘absence’ seizures). Doctors can describe seizures by what’s happening on the outside (what one can “see”) or sometimes by what’s happening on the inside (for example, the type of seizure pattern on the EEG) or both. Patients with KCNMA1-linked channelopathy can have none, or all, of many different seizure types. Sometimes, more than one seizure type can occur at the same time or one right after the other. Seizures can start at any age, and any one seizure type can come and go at any age.

Developmental Delay

Children with KCNMA1-linked channelopathy may have normal development and intelligence. They can learn to sit, stand, walk and talk at the same time as other children. But usually, children who have frequent epileptic seizures tend to develop more slowly than other children.

What other problems might people with a KCNMA1-linked disorder have?

Since there are so few patients that we know about who have this condition (only about 50!), it is very possible that there are other symptoms that are not described here. Anyone diagnosed with a KCNMA1-linked channelopathy is encouraged to contact the KCNMA1 Channelopathy International Advocacy Foundation to help neurologists and scientists better define the symptoms and responses to standard therapies.

How serious is a KCNMA1-linked condition?

There are many people with a KCNMA1 mutation who have minimal or no symptoms. There are yet others who have serious problems which negatively affect their health in direct ways, and there is everything in between. Different mutation types can cause different types or severity of symptoms. But even people with the identical mutation can have very different symptoms. In addition, symptoms can change over time in the same person, sometimes getting better and sometimes worse.

How common is KCNMA1-Linked Channelopathy?

This is a very rare condition. It is estimated that less than 1 in 100,000 people are affected. But we are finding newly diagnosed patients regularly, so it may be a little more common than we think.

In whom does KCNMA1-Linked Channelopathy occur?

Because it is a genetic mutation, KCNMA1-linked channelopathy is already present before birth, even if symptoms might not start until much later.

What causes KCNMA1-Linked Channelopathy?

It is caused by a mutation/defect in a gene called KCNMA1 on chromosome 10. This gene is responsible for making one of the hundreds of different proteins that makes sure the electrical activity of brain, nerve, heart, and muscle cells is working correctly. This is why many of the symptoms involve the brain and muscles. Different types of KCNMA1 mutations have been identified in patients with this condition and each mutation can lead to a unique set of symptoms. It is also possible for patients who share the same KCNMA1 mutation type to experience different symptoms.

De Novo (New) KCNMA1 Mutation

Currently, most KCNMA1-linked channelopathy patients have ‘de novo’ mutations, which means the mutation in the KCNMA1 gene randomly happened in an egg or sperm but which did not come from either parent.

Autosomal Dominant (Heterozygous) vs. Autosomal Recessive (Homozygous)

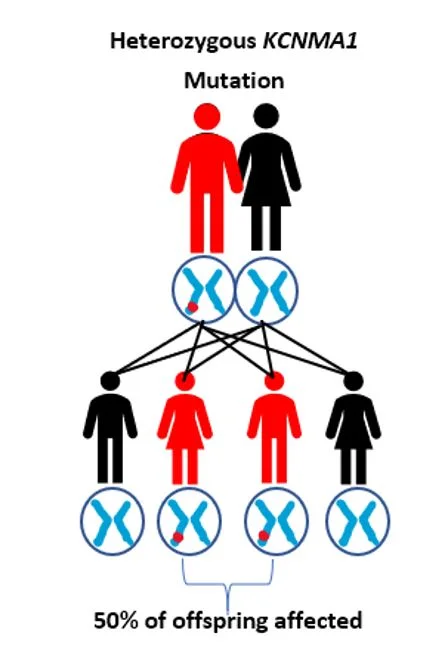

KCNMA1-linked channelopathy is most frequently found to be an ‘autosomal dominant’ or heterozygous mutation, that is, it only requires that there is a problem in one of the two KCNMA1 genes we all have. In contrast, an ‘autosomal recessive’ or homozygous mutation requires that both copies of this gene have a mutation in order to cause symptoms. There are only a few people known to have a recessive KCNMA1 condition.

Can a KCNMA1 Mutation be inherited?

There are a few known patients diagnosed with a KCNMA1-linked channelopathy, where the mutation was inherited from a parent. Children from an adult with the dominant form of this condition have a 50% chance of inheriting the mutant gene. However, despite potentially having the same mutation, it is not possible to predict whether the child’s symptoms will be the same as the parents. The symptoms could be similar, milder or more severe. In those with the autosomal recessive or homozygous form, it would be rare that any of their children will inherit this condition. It would require the other parent to also have a problem with the KCNMA1 gene. This would be very unlikely given how rare mutations in KCNMA1 are. But if indeed both parents had KCNMA1 mutations, each child would have a 25% chance of inheriting both abnormal KCNMA1 genes. For more information about genetics and inheritance patterns please visit this page.

Incomplete Penetrance of Symptoms

‘Penetrance’ refers to the degree of symptoms a patient experiences for a genetic mutation. Not every person who has an error in the KCNMA1 gene experiences symptoms. Some people carrying a KCNMA1 mutation may never experience symptoms during their lifetime. This phenomenon is referred to as incomplete penetrance.

What does the KCNMA1 gene do?

The KCNMA1 gene contains information for the construction of a specific type of protein needed in cells of the body. This protein is needed to make sure that the electrical signals in cells, including the brain, heart, and muscles, work properly. The protein encoded by KCNMA1 is an ‘ion channel’, which is a type of tunnel which allows ions to flow across cell membranes and which thus causes or modifies electricity in cells. Specifically, KCNMA1 makes a unique type of channel that allows potassium (K+) ions to flow through the channel. The KCNMA1 channel has many names, and is often referred to as the ‘BK’ (‘Big K+’) channel. BK channels have special properties, in that they become active when a voltage change is detected while there is also a different ion (calcium) ‘touching’ or binding the channel at the same time. Because of this unique type of activation, KCNMA1 channels play an important role in the electrical activity of brain and muscle cells. KCNMA1 mutations which make this ion channel function abnormally can in turn lead to abnormal electrical activity of the brain or muscles. This is why problems in any of the many kinds of potassium channels can cause epilepsy and movement disorders.

What is the function of a potassium channel?

Potassium channels’ major function is to control the movement of potassium ions in or out of cells. By doing so, these channels help set the voltage across a cell’s membrane and influence the electrical communication between cells. When activated, most potassium channels (including the BK type made by KCNMA1) allow potassium ions to flow out of the cell which causes the voltage to become more negative and essentially “turn off” the function of that particular cell. In a way, potassium channels acts like a “brake” to stop that cell and prevent it from being active at the wrong time or in the wrong way. With some KCNMA1 mutations, the BK potassium channel does not work properly, and thus any given cell may be more active than it should be. Or the opposite may occur, with the cell being less active than normal. The summary is that this affects the overall balance of communication in the brain, nerves, or muscles, and this can cause the many symptoms seen in KCNMA1-related conditions.

What does KCN of KCNMA1 stand for?

‘KCN’ is the acronym given to genes that encode the different types of potassium (K+) channels found throughout the body. Any “class” or type of potassium channel can control the movement of potassium ions in or out of cells. But the conditions under which the channels are active/open can be very different depending on the specific channel class. The symbols that follow KCN provide more detail about the specialized features of a particular class of potassium channels. For example, ‘KCNM’ and ‘KCNN’ genes encode potassium ‘calcium-activated’ channels (i.e. BK) whereas ‘KCNT’ genes encode potassium ‘sodium-activated’ channels. To date, there are a total of 79 KCN genes identified and many have been linked to disease-causing channelopathies. See this page for more information about the different ‘KCN’ genes.

How many mutations have been found in KCNMA1?

While movement disorders and epilepsy are certainly very common conditions, it is only very recently that we learned that KCNMA1 mutations cause these symptoms. 15 disease-causing mutations have been described so far in the published literature, and many more have been provided by patients’ genetic reports. Currently, we know of about 50 patients from around the world that carry mutations in KCNMA1 and experience symptoms. If you would like to participate in the efforts to understand how mutations in KCNMA1 produce symptoms, please contact us.

How is a KCNMA1-Linked Channelopathy diagnosed?

Pregnancy and Birth

There are usually no clues during a pregnancy. Patients with KCNMA1-linked channelopathy typically have a normal birth weight and height, and the first few months of life are usually normal.

Patient Story and Research

If a patient suffers from severe seizures and/or involuntary movements at a young age with no clear cause for these symptoms, and is unresponsive to standard medical therapies, genetic testing will likely be suggested by a neurologist. Keep in mind there are many different medical conditions that can produce seizures and movement disorders. Patients with KCNMA1-linked channelopathy may also have other unrelated disorders that factor into the symptoms they experience.

Electroencephalogram (EEG)

When patients are thought to be experiencing seizures, typically the first diagnostic test performed is an EEG. This test records the electrical activity of the brain to determine if abnormal electrical activity is responsible for a person’s symptoms. ‘Generalized epileptiform abnormalities’ are one type of abnormality often seen on the EEG of patients that have KCNMA1-linked channelopathy. Among those with EEG abnormalities, so-called ‘generalized spike wave complexes’ with a frequency between 3-4 Hz are commonly seen. There are other abnormal waveforms detected by EEG that vary by amplitude, frequency, and duration depending on the type of seizure and location of the seizure in the brain. Keep in mind a normal EEG does not always rule out the diagnosis of seizures. In addition, there can are many abnormalities which can be seen on an EEG which are asymptomatic, or otherwise are not thought to be associated with epileptic seizures.

Brain MRI

In children with epilepsy and/or movement disorders, an MRI of the brain is often performed to see if any anatomical brain abnormalities might be contributing to a patient’s symptoms. However, the MRI scans in patients with KCNMA1-linked channelopathy are usually normal. This is because the problem is with how the brain cells work, but not with how they are arranged or what they look like in general.

DNA Testing

If other medical diagnostic tests fail to confirm a definitive diagnosis in cases of seizures or movement disorders, genetic testing can be performed to look for an error in genes related to neurological function. Several genetic tests are available called ‘Epilepsy Panels’, which now test for mutations in KCNMA1 as well as hundreds of other ion channel genes linked to epilepsy and abnormal movements. KCNMA1 mutations can also be found with a genetic test called ‘whole exome sequencing’. To obtain genetic testing, a neurologist will refer the patient to a genetic physician or genetic counselor, who orders the test and can help interpret the results. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing (i.e. 23andme or GeneSavvy) will not diagnose this medical condition.

How is KCNMA1-linked channelopathy treated?

Currently, there is no one standard treatment or set of treatments which is used in KCNMA1-related conditions. Each type of mutation leads to a different set of symptoms, and each type of mutation may have different treatments which might help with any of the many symptoms patients may have. In fact, people with the identical mutation may have completely different symptoms and even a different response to the same medications. It is very important for patients to work closely with their neurologists to investigate the best of the treatment options based on the individual symptoms experienced and their particular overall circumstances.

Treatment of Epilepsy

Medications referred to as anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) or anti-seizure drugs (ASDs) are usually the first steps in attempting to prevent seizures. There is a lot known about which particular seizure medications might work for a particular seizure type or in a particular medication condition. At this point, very little is known about all the various KCNMA1 mutations and which medications might work best (or at all) for a particular person. Keep in mind that each person with KCNMA1-related illness does not necessarily have the same condition! If medications fail to control the epileptic seizures after trying many different ones, there are other potential treatment options including a ketogenic diet (essentially a very very low carbohydrate diet) There is also a device called a ‘vagus nerve stimulator’ which can help some people.

Treatment of the Movement Disorder

There are also medications which can help with the paroxysmal dyskinesias and other abnormal movements. Certain medications (for example, benzodiazepines and acetazolamide) have been previously found to be helpful for some people with certain movement disorders which look the same as those in KCNMA1. Whether these or other medications might help those with KCNMA1-related movement disorders has not been determined.

Rest and Regularity

In general, poor sleep and stress can increase the risk or the amount of seizures or movement attacks, due to any diagnosis. This seems to also be the case in some people who have KCNMA1-linked channelopathy. That is why a regular daily routine with adequate sleep is something to aim for. ‘Stress’ (both good and bad kinds) are a part of daily life and cannot be completely prevented. It is important for all people to regularly incorporate rest and relaxation moments into the day, and this is particularly important for anyone with a medical condition.

Physical and Occupational Therapy and Safety

An occupational therapist can advise parents on how they can best help their children in stimulating development and individual development plans. A physical therapist can advise parents on plans for safety and mitigation of seizures and dyskinesia. People with paroxysmal dyskinesias and seizures are at risk for injury, and many will be advised to wear protective helmets in order to minimize the chances of an irreversible brain injury which can result from a fall.

Contact with other parents

While each child and family is different, there are certainly benefits to being part of a group of people dealing with similar issues. We encourage patients, caregivers, medical professionals and scientists to register for our discussion forums. There you can communicate with other patients/families dealing with KCNMA1-linked channelopathy. You can find the forums through www.kciaf.org, or you may go there directly through this link: http://www.kciaf.net.

Family Counseling

A social worker or psychologist can provide counseling on how having this disorder can interfere with the daily life of families. It often takes time for parents to process that their child’s expectations for the future look different than expected.

What does having KCNMA1-linked channelopathy mean for the future?

We don’t have a complete understanding of the KCNMA1-linked channelopathy because it is a fairly newly described condition, and few people are known to have the condition. However, we might expect that the prognosis or long-term outcome would be similar to other seizure and dyskinesia disorders. The oldest patient harboring a KNCMA1 mutation is in their 50s, suggesting that lifespan is normal. Laboratory mice harboring mutations in KCNMA1 can have normal lifespans, even while exhibiting symptoms of brain and muscle problems.

Ongoing Research

Current research is being conducted to understand how mutations in the KCNMA1 gene change the activity of the potassium channels it encodes. Further research is geared toward understanding how brain activity may change with these mutations. If patients or families would like to contribute to this research effort, please email us through www.kciaf.org and we will provide you with further information.

What about ‘precision medicine’ and therapies that would specifically correct the KCNMA1 gene defect or the abnormal function of the channel protein?

At present, not every mutation in KCNMA1 has been verified to produce a change in the ion channel activity, or in brain or muscle activity, in a way that neurologists and scientists understand. Therefore, it is not possible to choose a drug that can specifically correct the KCNMA1 defect at this time. Several research efforts are underway to find new drugs that might be able to compensate for the symptoms of the KCNMA1-linked channelopathy, but the current recommendation is to work with neurologists and movement disorder specialists using known medications with known safety profiles. As research progresses, KCIAF will communicate any new knowledge to the patient community.

An initial version of this text and figures were taken from this page, written in the Dutch language by Dr. Jolanda Scheiving, a pediatric neurologist working at the Amalia Children’s Hospital. Dr Scheiving graciously allowed us to modify and expand it for use by KCIAF.org.

Note also that this page is intended to be only general information and education on KCNMA1 disorders, and is not intended to suggest any particular treatment or specific recommendations for any particular person.